"A reality is just what we tell each other it is. Sane and insane could easily switch places...

You would find yourself locked in a padded cell, wondering what happened to the world..."

“This is reality” Sam Neill’s character John Trent insists, wide-eyed and disbelieving that his life is “not fiction.” He is a man in control of everything, and overly confident that he is the master of his own fate. The statement could be read as a tagline for John Carpenter’s 1994 film “In the Mouth of Madness”: What if fiction and reality were indistinguishable?

Often cited as the concluding chapter in Carpenter’s loose “Apocalypse Trilogy,” following “The Thing” (1982) and “Prince of Darkness” (1987), “In the Mouth of Madness” marks a strange, cerebral detour in the director’s career. While those earlier films explored annihilation through science or faith, the third film turns inward, confronting the apocalypse of the mind towards the end of the 20th century. It depicts a world collapsing under the weight of narrative itself.

At its surface, the story resembles a straightforward detective tale, at times flirting with neo-noir tropes. An insurance investigator John Trent (Sam Neill) is hired to locate a missing novelist, Sutter Cane, whose horror books have become a cultural phenomenon. But as Trent’s investigation leads him to the fictional town of Hobbs End the film’s layers begin to unravel. Carpenter peels back the illusion of narrative logic until nothing remains but madness.

Neill delivers one of his finest performances, oscillating between scepticism and unhinged despair. Having already explored spiritual collapse in Andrzej Żuławski’s brilliant horror “Possession” (1981) and later in the cosmic terror “Event Horizon” (1997), Neill brings a physicality to Trent’s breakdown that is both absurd and tragic. He laughs, mocks, and screams, yet beneath the performance lurks a growing awareness that every gesture has been scripted, every line already written by another hand. By the third act, Trent has no choice but to embrace the insanity of it all.

Carpenter’s structure mirrors the best of HP Lovecraft’s storytelling. Its structure resembles many of the horror writers’ stories; the confession from the asylum, the flashback, the circular revelation that the end has already happened. The film’s brilliance lies in its rhythm and dramatic hindsight. At barely over ninety minutes, it unfolds like a fever dream that somehow respects economical filmmaking.

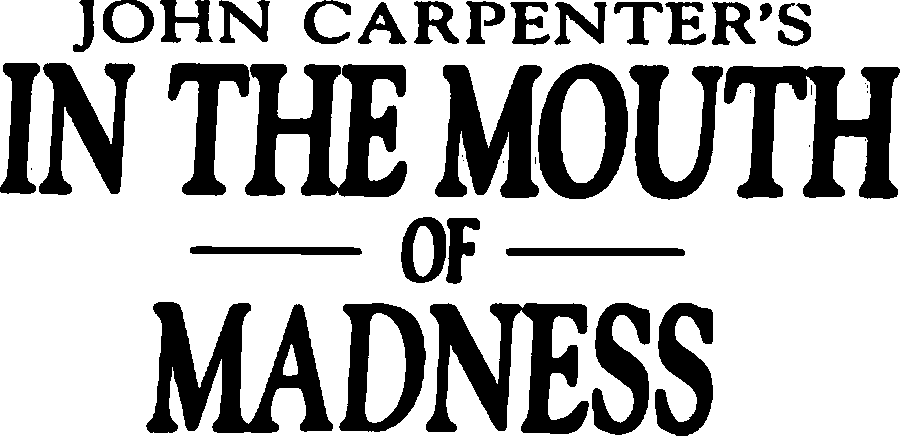

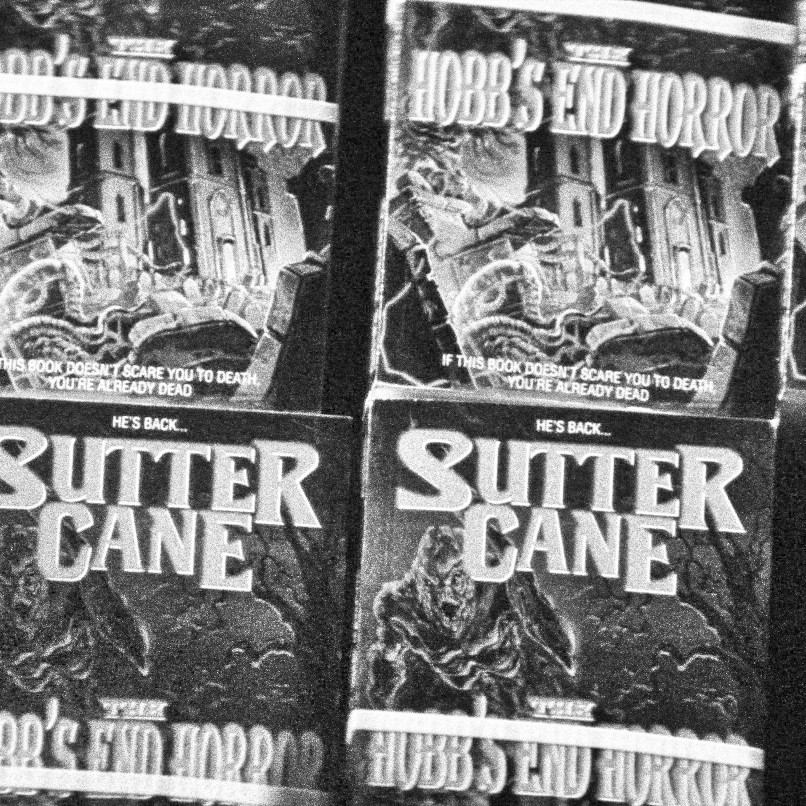

The meta-horror at the film’s core is both playful and profoundly unsettling. Sutter Cane (Jürgen Prochnow of “Das Boot” fame) is clearly modelled on Stephen King, yet he represents something larger. He shapes the world through his imagination. His books, we are told, are so popular that they distort collective consciousness. “I think, therefore you are,” he tells Trent, reversing the order of creation. In this world, fiction no longer imitates life but replaces it. However, upon further inspection, we learn that Cane may be a puppet for some gargantuan cosmic entities.

Carpenter and screenwriter Michael De Luca approaches this concept with surprising sophistication. The film anticipates the self-reflexive horror that would define the late ’90s (think “Scream” or “The Blair Witch Project”). Its meta-commentary is not ironic; it is totally existential. Earlier in the film when Trent smears ink across his face, it’s not simply a visual flourish but a symbolic act, a literal mark of authorship. He is becoming text. The idea that one’s reality could be authored, that free will be a literary illusion, is a horror more profound than any creature crawling from a church crypt. Hence the numerous Lovecraft comparisons.

The Byzantine church of Hobbs End, incidentally, is one of the film’s most striking images. A structure rising over a rural landscape, impossible in both scale and geography. It’s a visual metaphor for the story’s architecture. It is ornate, alien, and collapsing under its own impossibility. The surrounding town of Hobbs End feels like it exists in a liminal space, as though drawn hastily into being by Cane’s pen. The film’s set design plays with the uncanny geography of dreams, where roads loop back on themselves and time folds inward. The interior includes endless halls and pulsating walls.

The monsters are glimpsed only briefly in the half-light, but they are pure Carpenter. Tentacled, fleshy, and disturbingly organic, they echo “The Thing” but with a mythic undertone. They are not simply aliens or mutations. Their reveal suggests their majesty to Cane, who works as their harbinger of doom. Carpenter wisely refuses to linger on them, understanding that the true terror lies not in what is seen, but the sole existence of such a thing.

The film’s soundtrack is another highlight. Co-composed by Carpenter and Jim Lang, the score opens with a riff unmistakably inspired by Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” (supposedly as the band did not allow for the use of their music in the film). The heavy guitars lend the film a sardonic edge, a reminder that Carpenter’s apocalypses are as much about dark humour as despair. His worlds end not with solemnity, but with a smirk and a scream. It is heavy metal film making by a master.

The Sutter Cane/Stephen King parallel adds another layer of meaning. In the early ’90s, King was not just an author but a cultural institution, shaping the popular imagination of horror. By invoking that shadow, Carpenter blurs the line between satire and prophecy. The film suggests that mass-market storytelling, endlessly reproduced and devoured, might itself become a kind of contagion, a collective hallucination indistinguishable from truth. To Trent, this is absurd, but he becomes fascinated when he eventually picks up the books of Cane. Later in the film, Canes publisher (played by Charlton Heaston of all people) tells Trent that the film production will reach those who do not read. This is of course within the meta, as the film we are watching turns out to be the film they are talking about, however the idea that a huge author in the 1990’s wasn’t being consumed because people simply didn’t read anymore, is an interesting side note.

Watching “In the Mouth of Madness” today, its prescience feels almost eerie. Long before social media algorithms, Carpenter foresaw a world where belief could be manufactured, and reality could fracture under the weight of its own narratives. The film’s final image, Trent sitting alone in a cinema, laughing hysterically as he watches his own story play out on screen, now feels like a metaphor. The audience consumes the apocalypse and mistakes it for entertainment.

“In the Mouth of Madness” is less a horror film than a philosophical nightmare. It invites us to question who or what is writing the story we inhabit. Its terrors are intellectual and emotional, existential, and absurd. It is a film about the seduction of fiction and the horror of realizing there may be no exit from it.

Carpenter’s genius here lies in restraint. He does not explain the madness, because explanation would be a form of control. In his hands, horror becomes not an interruption of reality but its inevitable revelation. The monsters were always there.