"Evolution brings human beings. Human beings, through a long and painful process, bring humanity...”

Dan Simmons’ “Hyperion” is one of those rare science fiction novels that feels at once monumental and intimate. A canvas of stories built on the oldest foundations of storytelling itself. While it sprawls across planets in the far future, its heart belongs to a campfire tradition older than any machine. This review is not an exhaustive analysis of a nearly thousand-page epic or its subsequent follow ups, but rather an appreciation of its most striking qualities; the way it reclaims the art of storytelling as both structure and soul.

Simmons 1989 epic takes inspiration from “The Canterbury Tales”, reimagining CHAUCER’s pilgrims as seven travellers journeying to the distant world of Hyperion, where a mysterious being known as the Shrike waits for them. Each traveller tells a story to explain why they are making the pilgrimage, and through these stories, the novel becomes a living archive of human imagination. JOSEPH CAMPBELL’s “The Hero’s Journey” is invoked, yet we as the reader do not entirely reach the destination, rather are described a world and society through the origins of the characters. Simmons fuses medieval literary architecture with a futuristic setting, using that blend to remind us that all stories, no matter how advanced their worlds, are retellings of ancient myths about fear, faith, love, and mortality.

What makes “Hyperion” extraordinary is the variety and confidence of its voices. Each tale has its own tone and genre. The Priest’s Tale evokes the horror journal of “Dracula”; the Detective’s Tale story feels like a smoky noir that could have been written by PHILIP K DICK; the Soldier’s Tale echoes the ironhearted fatalism of “Starship Troopers”. These shifting modes do more than keep the reader enthralled, they become a commentary on the act of storytelling itself, suggesting that genre is simply another dialect through which humanity explains its own fragility.

Simmons’ prose deserves its reputation for beauty. The influence of JOHN KEATS, whose poetry haunts the novel both thematically and literally, is unmistakable. At its finest moments the writing approaches the lyrical intensity of Keats’ odes, full of longing and melancholy, where technological marvels coexist with mythic wonder. The tension between the mechanical and the poetic, the cosmic and the human is where Simmons finds emotional gravity in the story.

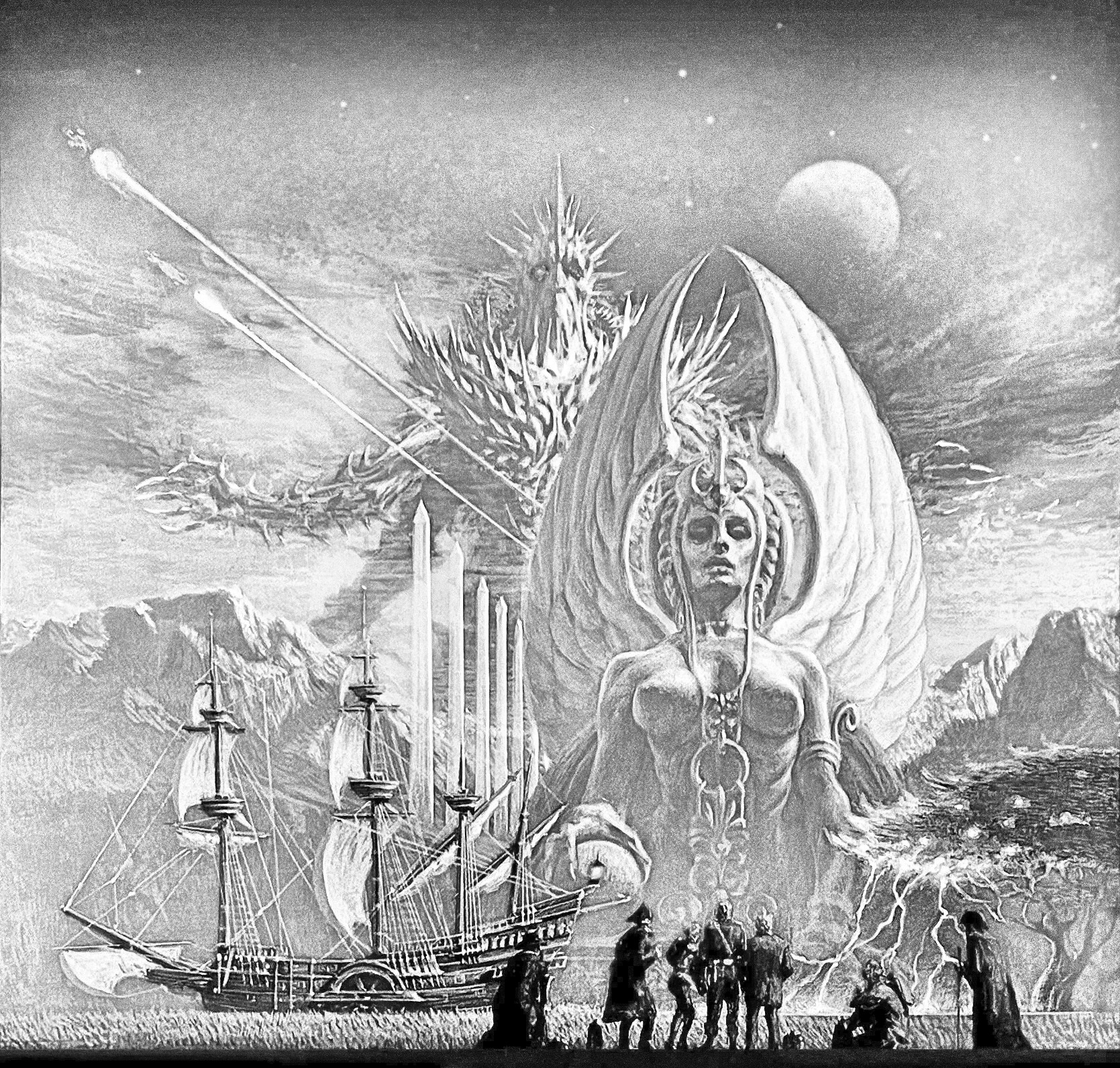

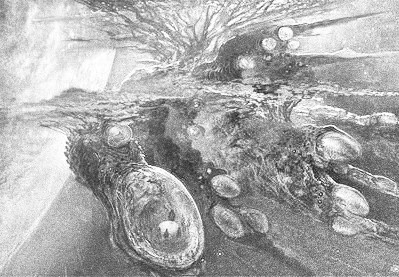

THE SHRIKE, the enigmatic creature at the novel’s centre, functions as both a literal monster and a symbolic presence. It is terror made flesh, an embodiment of humanity’s need to confront mortality headfirst. The Shrike’s unpredictable appearances lend the book a mythic quality, as though it were a modern incarnation of the furies or death itself. Each character’s path to the Shrike becomes an allegory for the confrontation with fear, the point at which human intellect fails and only faith or acceptance remains.

Simmons balances these lofty ideas with precise craftsmanship. His universe feels vast yet tactile, governed by believable politics and philosophy. It is no surprise that many have speculated about adapting “Hyperion” to film or television, yet it may be too intricate, too fluid in tone, to survive translation. Each tale depends so deeply on its narrative voice that to compress or homogenize them would strip away the novel’s essential rhythm. “Hyperion” is not merely a story but a chorus of stories, and its power lies in the friction between them.

Comparisons to other works of science fiction are inevitable but illuminating. Where “Dune” explores empire through mysticism and ecology, and “The Left Hand of Darkness” contemplates identity through anthropology, “Hyperion” examines humanity through its compulsion to tell stories. It reminds us that narrative is not just entertainment but survival. The pilgrims’ voices sustain them against the uncertainty of the journey, just as readers use fiction to orient themselves within chaos.

The novel concludes with what might be one of the most audacious endings in science fiction. It concludes almost abruptly, just as the pilgrims reach their destination, with a tone both eerie and absurd. It references “The Wizard of Oz” in an ambiguous way. The effect is haunting, at least to me. After hundreds of pages of storytelling, the book refuses closure, forcing us to confront the unending nature of narrative itself. Every story, Simmons suggests, is only a fragment in a larger cycle of creation and retelling. I imagine Simmons knew he was to continue the story with “The Fall of Hyperion” a year later. But reading “Hyperion” as a standalone, still works.

Three decades after its publication, “Hyperion” endures not merely as a landmark of speculative fiction but as a meditation on why we tell stories at all. Beneath its labyrinthine structure and grand cosmic scope lies a profoundly human idea: that the universe, no matter how vast or mechanized, is bearable only when we can turn it into a tale. Simmons’ achievement is to make that old truth feels new again, as if language itself were still capable of pilgrimage.

“Hyperion” is not a book about the future but about the persistence of myth. It reminds us that even in an age of machines, we remain storytellers walking toward the unknown, carrying our fears, our faith, and our words like offerings to our own SHRIKE.